By John Erich

Lexipol Staff

celebrates its 20th anniversary in 2023, but the roots of the company stretch back even farther – in some key ways as far back as the 1970s.

For many law enforcement agencies in the U.S., the 70s were a less structured time. What departments had in the way of policies were often static, dated documents committed to binders, then forgotten on shelves. They may have developed these policies themselves, based on their own best practices and understanding of the law, or simply borrowed them from elsewhere. That meant they could vary in important ways from one jurisdiction to the next.

That was a nagging problem that became crystallized one day for a young California Highway Patrol motorcycle officer named Gordon Graham. Graham had fallen into the kind of pursuit that was frustratingly common for police in the mid-’70s: The suspect was on a high-powered Japanese bike that could easily outpace CHP’s older Harleys. But when he ran, Graham chased, operating within CHP’s pursuit guidelines as they wound through the busy Los Angeles metro.

Soon other hounds were on the hunt. Officers from the Los Angeles Police Department, which had only recently ceded enforcement on L.A.’s freeways to CHP, joined the chase. So did deputies from the L.A. County Sheriff. As the caravan wound west, so did police from Santa Monica. And nobody, it turned out, was working from quite the same playbook.

“I later learned,” said Graham, “that the Los Angeles Police Department’s policy on chasing people was completely different than the CHP’s policy. And then Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department’s policy was different than LAPD’s and the CHP’s. And Santa Monica’s policy was different than everyone’s.”

Graham was working on a master’s degree in safety and systems management at USC, so he knew a few things about risk – and this didn’t sit right. California and federal laws were the same for everyone – so why did everyone have their own way of doing business? Certainly, some departments’ policies were safer and sounder than others, but having endless variations didn’t seem the best way to protect anybody – officers, suspects, or citizens.

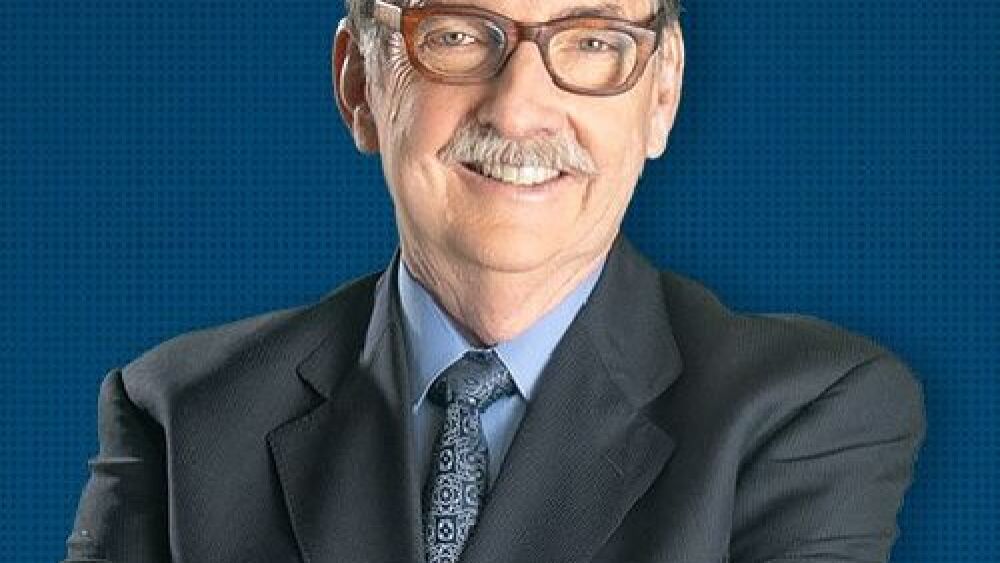

“One of the things they taught me in graduate school,” Graham said, “is that if you want to be successful, you standardize best practices and don’t deviate.”

An answer finds a need

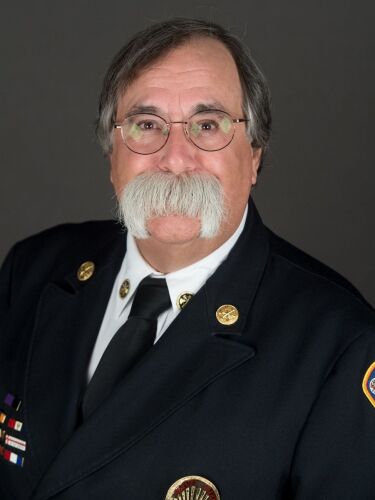

As the ’70s turned to the ’80s, Graham wasn’t the only bright young criminal justice mind in Southern California thinking about police policy. In 1973 Bruce Praet, then 19, had become the first cop under age 21 hired in California – a result of a change in state law. He served in Laguna Beach, then the city of Orange, in a variety of roles, including as a K-9 officer.

The death of a beloved canine partner helped push Praet toward law school, where he became an attorney dedicated to defending police in court. Through this work, he had frequent contact with departments’ policies, such as they were.

“Over several years I kept seeing, to use a Latin phrase, nothing but crap out there for policies,” Praet said. “Departments would borrow other departments’ policies and just plug their names in, and they’d be outdated policies that didn’t fit that new agency.

“The turning point came when I was defending an agency on a shooting and called the chief for a copy of their use-of-force policy. He called back and said, ‘I found two policies, one from 1968 and one from 1975.’ This was the late ’80s, and neither of them were anywhere close to current legal standards. I thought it was embarrassing!”

With help from colleague Geoff Spalding, then a deputy chief with the Fullerton PD, Praet set out to create a solution. He hunkered down and spent a year writing a complete police policy manual from scratch. Through his law firm, Santa Ana-based Ferguson, Praet and Sherman, he offered the product to a few initial police clients. They loved it, and so did their insurers. As a bonus, the firm offered to keep the manual updated for those clients, sparing them the cost and burden of hiring someone to do it.

That was a nice perk but a workload that ballooned quickly as more clients signed on. “We’d send agencies 300 printed pages, and they’d attach Post-it notes and redline them and FedEx them back, and we’d make the changes – it was an archaic method of updating,” Praet said. “I decided we had to take this out of the law firm and make it independent.”

Ultimately Praet contacted Graham, an old friend from the lecture circuit who was by then breaking new ground in training officers via his short daily bulletins. Would he be interested in partnering on a new venture?

Making life safer and easier

Twenty years later the resulting company, , is a household name among U.S. public safety for its comprehensive offerings in the realms of policy, training, education, wellness, grants help and more, through which it serves more than two million public safety and government professionals in all 50 states. Graham’s and Praet’s initial idea for formalizing a policy shop for police has burgeoned into a broad suite of risk management solutions for public safety and local government that’s making life safer and easier for countless law enforcement, fire, EMS, corrections and local government personnel and the citizens they serve.

The driving focus behind this hasn’t been simply on providing policy, but on bigger concepts like education and helping departments improve.

“There are lots of companies that will sell you products, and that’s really not what we’re about,” said Chuck Corbin, who joined Lexipol as chief revenue officer in 2018 and became its CEO in 2021. “For us to move forward and thrive and really be the very best we can be, we want to focus on understanding first. We listen to our customers, understand their needs and provide them solutions.”

Policy remains at the heart of the company’s mission, but there’s far more to Lexipol now. Its offerings include:

- Fully developed for public safety agencies, researched and written by subject matter experts and vetted by attorneys. Lexipol policies address all operational areas and reflect national standards and best practices as well as state and federal laws and regulations. The company provides updates as state and federal laws change, reviewing more than 10,800 pieces of legislation in 2022. Agencies also receive regular policy-based training bulletins to keep personnel fresh.

- with a broad range of content and the ability to centralize and streamline the tracking of training hours (both online and off-) and maintenance of credentials.

- Customized support and guidance for law enforcement agencies seeking .

- with a proven track record of success. This includes grant-writing services, research, alerts and tools to submit and track applications. Lexipol’s in-house grants team helps agencies identify opportunities, develop narratives and assemble the components they need to apply. Since its inception the company has helped agencies and local governments achieve $400 million worth of funding.

- to help public safety personnel manage the stresses and challenges of their profession. An app allows various self-assessments and provides information on dozens of behavioral health and wellness topics, plus one-touch access to counseling from professionals and peers. It can be customized with agency resources and is entirely confidential. Lexipol recently added peer support and clinician training and certification to the Cordico wellness solution.

- Leading Police1, FireRescue1, SA���ʴ�ý, Corrections1 and Gov1 that offer breaking news coverage, thought-provoking articles and product information.

Solutions for the fire service

As ’s product offerings expanded, so did its target audience. In 2006 longtime fire-service leader Billy Goldfeder came aboard to spearhead expansion into policy and training solutions for the fire service.

Goldfeder came with an email list of 4,000 fire chiefs with whom he regularly communicated on safety and other important issues. He’d known Graham since 1998, when an initial meeting at a conference led to the creation of Goldfeder’s website . “Close calls” weren’t a metric that was commonly tracked in any emergency service, but they had a lot to reveal about risk – the reduction of which was a core of Lexipol’s mission.

“We can’t just learn from the tragedies,” said Graham. “It’s a better idea to learn from the mishaps, because they’re 30 times more frequent and much less severe. And it’s the best idea to learn from the close calls, because those are 300 times more frequent with no severity at all.”

Like police, fire department policy has traditionally been a piecemeal affair – due to both an overall lack of standards and the prevalence of volunteer services. Over the initial reservations of a few cautious colleagues, Goldfeder, Graham and other key players met to work out a fire business plan. Lexipol expanded its range of solutions to fire/rescue and found the need they anticipated.

“I always ask a simple question: Are we going to solve a problem no one else has been able to solve?” Goldfeder told a company audience earlier this year. “That’s what Lexipol is here for. We are here to help solve labor problems, management problems and leadership problems. We provide a safer community for officers, for firefighters and for civilians. We’re excited about it.”

Every day a training day

The last three years have been a challenging time for law enforcement. Events like the deaths of George Floyd and Tyre Nichols have generated skepticism of police and, increasingly, questions about how they’re trained for such difficult situations.

More than 40 years ago, Graham identified five pillars of organizational risk management: people, policy, training, supervision and discipline. When any organization suffers a bad event, leaders can look to these five elements for root causes. Training gaps, as we continue to see, are often a culprit. Policies that aren’t taught and reinforced regularly do little good. And personnel who aren’t physically and mentally fit for duty cannot provide the best service.

“For most public safety personnel, paramedics being the exception, you graduate the academy, and if you choose not to promote, you’ve taken your last test,” Graham noted. “That’s a shame. We need to make every day a training day for core critical tasks.”

Graham often cites the first rule of legendary naval leader Admiral Hyman Rickover: Seek a rising standard of quality over time, well beyond what is required by any minimum. The concept of continuous improvement – through policies, training and wellness – has become the hallmark. For departments that embrace it, the payoff is clear – getting better every day and regularly raising the bar for their personnel.

The benefits can be both quantifiable – agencies may see fewer complaints and absences and reduced worker’s comp claims – as well as less tangible but just as important in areas like public trust and support for the emergency services.

“It all goes to improving the profession, whether it’s firefighting, law enforcement or corrections,” said Praet. “Our goal is the preservation of life, and if we continue to improve the standards, the training and the personnel, ultimately it benefits not only the profession, but the community.”

About the author

John Erich is a career writer/editor with more than two decades of experience in emergency services media, currently serving as a project lead for branded content with Lexipol Media Group.