By Jordan Nathaniel Fenster

The Middletown Press

HARTFORD, Conn. — The state’s first full blown heat wave has descended and the kids are out of school ready to dive into the nearest pool, lake or ocean, even as safety officials are busily spreading warnings about the rise in deaths by drowning across the country.

Despite recent tragedies, Connecticut appears to be bucking that trend, however, having shown a decrease in drowning deaths among children here since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, drowning is the second leading cause of death nationally among children younger than 5, and the second leading cause of unintentional injury-related death among children ages 5 to 14. Nationally, “unintentional drowning death rates were significantly higher during 2020, 2021, and 2022 compared with those in 2019,” the CDC wrote in a recent pre-summer season warning.

But drowning deaths among children in Connecticut have edged downward in the same time period, local officials say.

According to data provided by the State Office of the Child Advocate, Connecticut lost 28 children to drowning in the five years between 2013 and 2018, an average of 4.6 per year. Between 2019 and 2023, there were 20 drowning deaths among Connecticut residents aged 17 and under, an average of four per year.

“Things have changed over the last five years. I don’t want to say ‘significantly,’ but they’ve changed for the better,” said Brendan Burke, Connecticut’s assistant child advocate. " Connecticut overall, when it’s age-adjusted, has the third-lowest rate in the country” for drowning deaths among kids.

In fact, while the CDC wrote that “rates were highest among children aged 1 to 4 years” nationally, that has not been true in Connecticut in recent years.

Between 2013 and 2018, 25 percent of child drowning deaths were ages 15 to 17, with 43 percent under age 5. Since 2019 the numbers flipped, with 45 percent of those who died as a result of drowning age 15 to 17, while 35 percent were under age 5.

Connecticut is also going against the trend where racial disparities in drowning deaths are concerned. While the CDC wrote that Native and African Americans make up the majority of child drowning deaths, that is no longer true in Connecticut.

Between 2013 and 2019, 53 percent of child drowning deaths occurred in white families, far lower than the 61.6 percent of the state’s total population. Since 2019, 65 percent of the children who died by drowning were white, which Burke said “is more consistent with our racial breakdown in Connecticut.”

“Around that time pre-pandemic, it was a big concern,” Burke said. Urban communities in Connecticut don’t tend to have as easy access to pools, he said, “but there are opportunities to correct this and I think the state has done a decent job with some of these programs do so.”

In Hartford, the city is trying to do just that, offering free swimming lessons for youth through a partnership with the YMCA. Between July 1 and Aug. 9, the YMCA of Greater Hartford is offering 100 free sessions to children ages 3-17 who live in the city.

“Nobody wants to lose a child,” Mayor Arunan Arulampalam said earlier this week at a media event announcing the new program. “To lose a child to drowning is just heartbreaking, and we know that kids in cities, like Hartford, are disproportionately impacted.”

Kristina Baldwin, director of Hartford’s Department of Families, Children & Youth, said “Black children are five-and-a-half times more likely to die through drowning deaths than other children, so this is critically important for our community.”

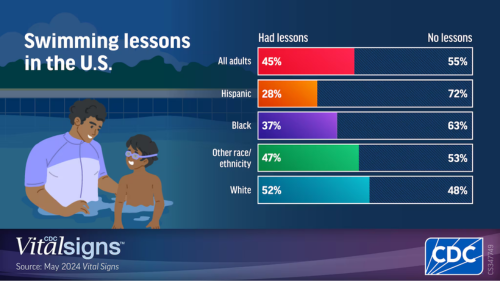

Of all adults surveyed by the CDC in their report, more than one-half reported they never took swimming lessons, with 72 percent of all Hispanics and 62 percent of all Blacks having no water safety training at all. That’s compared to 48 percent of all white adults who reported they’ve never had swimming instruction.

But lack of instruction alone isn’t enough to contribute to the high rate of drowning death rates among older teens.

When asked why teens made up such a large portion of child drowning deaths, Burke said it’s often the result of carelessness and overconfidence. Of the older teens who died by drowning between 2019 and 2023, 77 percent were in open water, such as a lake, river, pond or sea.

“We certainly see reckless behavior, jumping off bridges, things like that, where someone gets injured and then drowned because of that injury, or they’re out on boats,” Burke said. Suddenly, a fun outing quickly turns tragic.

North of Hartford, in the quiet suburb of Simsbury, Kristin Mabrouk is executive director of Hope Floats, which she said works with small swimming schools to provide scholarship funding and administrative assistance for children who might not otherwise have access to a pool or swimming lessons.

“I wasn’t prepared when I started this job for the stories I would hear from parents who lost a child to drowning,” Mabrouk said. “You think it’s not going to happen to you until it happens to somebody you know. It’s very common and for whatever reason, we’re not talking about it.”

(c)2024 The Middletown Press, Conn.

Visit The Middletown Press, Conn. at www.middletownpress.com

Distributed by