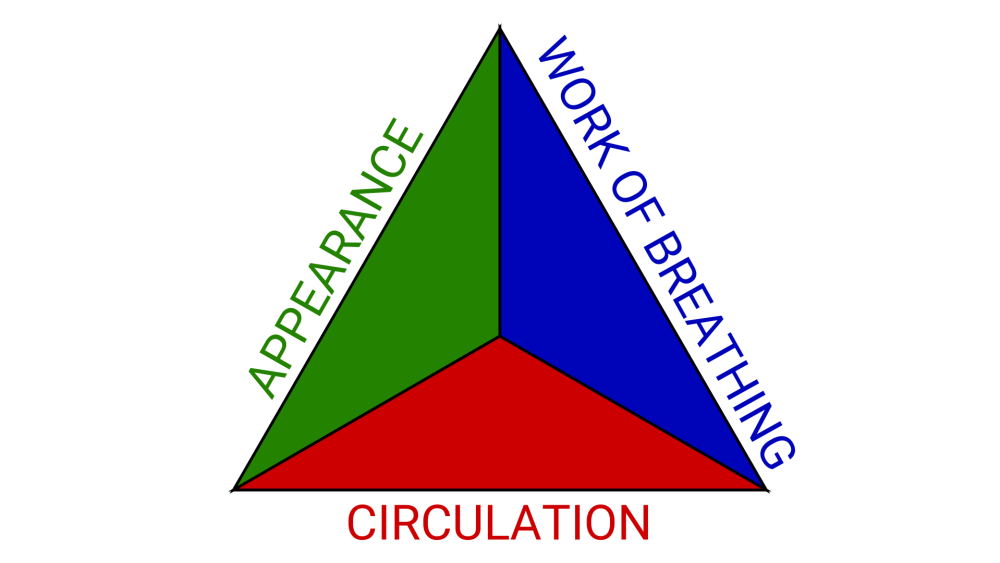

As we know, the pediatric assessment triangle is often used, rightfully so, as a tool to quickly identify sick kids who may require rapid, lifesaving intervention. While certainly effective for pediatrics, we can apply the same principles to the adult population to identify sick vs. not sick, and to rapidly form our initial impression and begin to form our differential diagnosis.

The three sides of the pediatric assessment triangle: appearance, work of breathing and circulation, can be quickly assessed as you walk through the door to greet your patient.

Appearance

As you enter the room, does your patient acknowledge you? When you say, “Hello sir/ma’am, my name is John, what’s going on today?,” any response other than, “Hey John, this is my chief complaint” is potentially a clue.

- Do they look at you and track you as you walk in the door?

- Is their speech slurred?

- Do they have facial droop?

- Is someone who is normally articulate and alert now slumped over and barely answering?

- No response is even more of a clue

Appearance refers to the patient’s tone and level of activity, or level of consciousness. More than just traditional AVPU, you can begin to assess orientation and capacity. Remember that orientation and capacity are more than just name, date, president and event. This is more than just how the patient looks, as well.

Look for clues in the patient’s vicinity, such as recent hospital discharge paperwork, drug paraphernalia or medications. It is also important to keep in mind scene safety when assessing a patient’s appearance. Move couch cushions and bed pillows, look at coffee tables and bedside tables. Be proactive in noticing firearms, knives or anything else that may be used as a weapon. You may be able to glean additional information from the contents of trash cans nearby, whether it be noting the bloody or coffee ground emesis in them, or the multiple empty OTC medication boxes.

Going into a scene, be nosy, not intrusive, but be truly aware.

Work of breathing

What is the patient’s respiratory rate and effort? A respiratory rate of 16 is considered “normal,” but not without adequate tidal volume. Minute volume matters.

- Is the patient tripoding?

- Can they speak in full sentences?

- Can you hear them wheezing as you enter the house?

- Do you note rales from the doorway?

- Are they sitting up truly working to breath?

- Are there retractions?

- Are they using accessory muscles?

Rapid recognition of and intervention in severe respiratory distress is vital. You do not need a pulse oximeter to tell when a patient is short of breath. Do not delay treatment for a “room air sat.”

Circulation

Skin condition is a relatively reliable predictor of perfusion. As a partner told me once, you can’t fake sweat. If someone is diaphoretic for no obvious environmental reason, it is time to investigate. In , in the presence of typical or atypical chest pain, the presence of sweating predicted the probability of STEMI even before clinical confirmation.

The eyes can tell a story, as well, with jaundiced sclera or pale conjunctivae possibly indicating liver disease, gastrointestinal bleeding or other blood loss.

- Are the patient’s pupils equal?

- Pinpoint?

- Dilated?

- Is the patient looking at you and tracking you with their eyes?

Rapidly reading a room and performing a quick visual evaluation of a patient from the doorway helps to identify potential life threats, to you and your patient. This, coupled with attention to detail makes narrowing down a differential diagnosis more accurate, which leads to better patient outcomes.

This article, originally published on April 03, 2023, has been updated.